July 24th, 2020. Taken from here

Recently Yasir Qadhi posted a video on youtube in response to Jay Smith regarding the dialectal differences between different Qur’anic readings, or Qira’at1. After years of controversy between Shabir Ally, Smith and other Christian apologists it seems that the issue of Qur’anic readings has come to the forefront. Qadhi and Ally maintain that while there are dialectal differences in the Qur’anic readings, this does not contradict the central theology of the text and Islamic doctrine more broadly. This seems like a very reasonable statement at face value, and one wonders to what degree this statement was necessitated.

In fact, Gabriel Reynolds says that the common belief among “less well-informed Muslims”2 that the Qur’an is perfect and unpreserved, without alteration (Tahrif), is a relatively modern one. Jay Smith also says this in his video3 on the Canonization of the Hafs reading in 1924 by the Egyptian government. I think in terms of the Islamic doctrine overall, we should give some credence to Qadhi and Ally in that the central dogma of Islamic theology is not changed because most of these differences seem grammatical. While I am generally sympathetic to Smith’s methodology and polemics, I feel that he places too much stock on the relevance of these differences to Islamic theology.

This criticism of the focus on minutae and pedantry on Qur’anic grammar may sound like an endorsement of the Traditional Islamic position, but it is far from it. In fact, the statement that Qur’anic changes do not affect Islamic theology is actually a strike against the Tradition, for this suggests that Islamic theology has little to do with the Qur’an to begin with. This notion had already been suggested by Crone & Cook in 19774 and more recently by Nevo, Donner, Schoemaker and the German school (Luxenberg, Puin and co.)5. I am planning on outlining a re-reading of Islamic history under this “new” thesis in a separate series, though I will use some of its conclusions here, as I would like to focus on the formation of the Qur’an and the relevance of the controversies surrounding it.

The Context

Beginning with Crone and especially Donner6 and Shoemarker7, the revisionist school of Islamic theology says that the movement of the Prophet “Muhammad”8 was an eschatological one focused on Palestine, and not on the Hijaz.

In sum, we have three basic facts:

(1) The vast majority of the randomly associated dialectal variations between Hafs and Warsh do not change the central theological doctrines of Islam, because–the text itself has nothing to do with Islam to begin with!

(2) Radiocarbon dating of the earliest Qur’anic folios or Mushafs–many of them fragments or Surahs, and most of which when combine form a complete “proto-text”, gives dates from the 5th-early 7th Centuries. This is well too early for the supposed revelations to the Prophet. Only later do complete Qur’anic corpi appear. At first, this seems like a contradiction–how can the Qur’an exist in disparate forms, yet they exist in self-contained Surahs? For example, an anonymous 8th-C. “dialogue with a Monk of Bet Hale” says that the Muslims follow the “Book of the Cow” (presumably a proto-form of Al-Baqarah, Surah 2) as though it was a text complete unto itself9.

(3) The Believers’ movement in the early Arab Empire was an ecumenical confederation (in Aramaic: Qurays) of different tribes of Arab monotheists convinced it was to play a part in the eschatological drama soon to unfold on the Temple Mount (in Arabic: al Masjid al Haram). Jesus would soon return at His Second Coming and herald the apocalypse once the Kingdom of David is re-established, as the usual (post)Christian eschatology goes. These disparate groups, while united in their common struggle against Rome (and to a lesser extent Persia), were divided by faith and tradition. Each had their own circulating texts, many of these being heterodox as they lay outside the bounds of organized Judaism and Christianity. Each of these texts were complete unto themselves and may have formed part of a “reading circle” as most of these people were nomads.

The Model

We can resolve the apparent paradox between (1) and (2) if we consider that the various source documents that were dated up to the early 7th Century are in fact the source documents of these groups, rather than a Qur’an itself. The source documents are complete and yet self contained because the Qur’an was compiled therefrom.

Now onto the question of the reason for the Qur’an’s compilation. I suspect this may have had something to do with ‘Abd Al Malik as his Dome of the Rock mosque have many verses which seem Qur’anic yet do not appear in our modern Qur’an10.

Why would he need to compile this book? Recall that the Arab Empire had been just ravaged with two civil wars, one from 656-661, the second from 680-692. The young Empire threatened to tear apart and the warring factions did not have a unified vision though the elites leading them were all Arabs. The Caliph probably took upon himself to use this fact and unite them with a common purpose and identity. At this stage, however, this identity was not yet Islam, as even many revisionist scholars think. It was still a form of the Abrahamist ideology propagated by the Prophet and his followers as they led the (post)Christian deliverance of the Children of Israel from the Romans. But factions were slowly forming. On one side were the Believers sympathetic to Judaism and intent on preserving the legacy of the Arabs in the newly conquered Holy Land, the other post-Christians in Hira mourning the theft by Mu’awiya11, of the Viceroyship (Caliphate) that was promised to the Risen One, Jesus Christ (the ‘Ali) who never came, as as originally prophesied by the Prophet. The latter group called themselves the Partisans of the Risen Christ (the Shiat’ul-‘Ali). (More on this to come in my series on Islamic origins.) To mend these divisions and make them think of themselves as Arabs, ‘Abd Al-Malik likely took inspiration from or directly borrowed Jewish source material and Christian source material in addition to local Abrahamist traditions, and perhaps Samaritan ones and others, that were held dear to the Arab believers.

The reason these sources complemented, rather than contradicted, one another, he maintained, was that they proved the Arabs had a role to play in salvation history. For most of history this desert people lay on the margins of both the Greco-Roman and Biblical dramas. Yet according to the Abrahamist ideology of unknown origin, at least some of the Arab believers also recognized themselves as cousins of the Jews, as both were descendants of Abraham. The Qur’an is at pains to prove that it is merely confirming the legal covenant (Deen, meaning judgment12) that came before and was granted to Abraham (Surah 61.913) by God as well as his descendants, the Jews and Christians. These source materials are then, in the first phase of redaction, meant to now be read together as a midrash on the Bible14: thus, it is not meant to supplant but merely confirm the earlier Scriptures (3.315). Hence why its frequent allusions to Biblical and extra-Biblical stories are just that: allusions. It was not yet viewed as a Scripture unto itself.

So this book, soon to be known as al Kitaab (the Book), became the glue that literally bound the Empire together as through its pages the Arabs searched and found for themselves proof of their role in History. In it are Signs from God that make clear that the Book is a message proving to the Arabs their inheritance (3.716).

Postscript N.: If we consider the instances of “Al Kitaab” being mentioned in the Qur’an really referring to the original Book of ‘Abd Al Malik, since he obtained his sources from the writings and scriptures of the “Peoples of Abraham”, then it makes sense that they are called “People of the Book”. Here, then, the Book refers to the Kitaab, not the Bible.

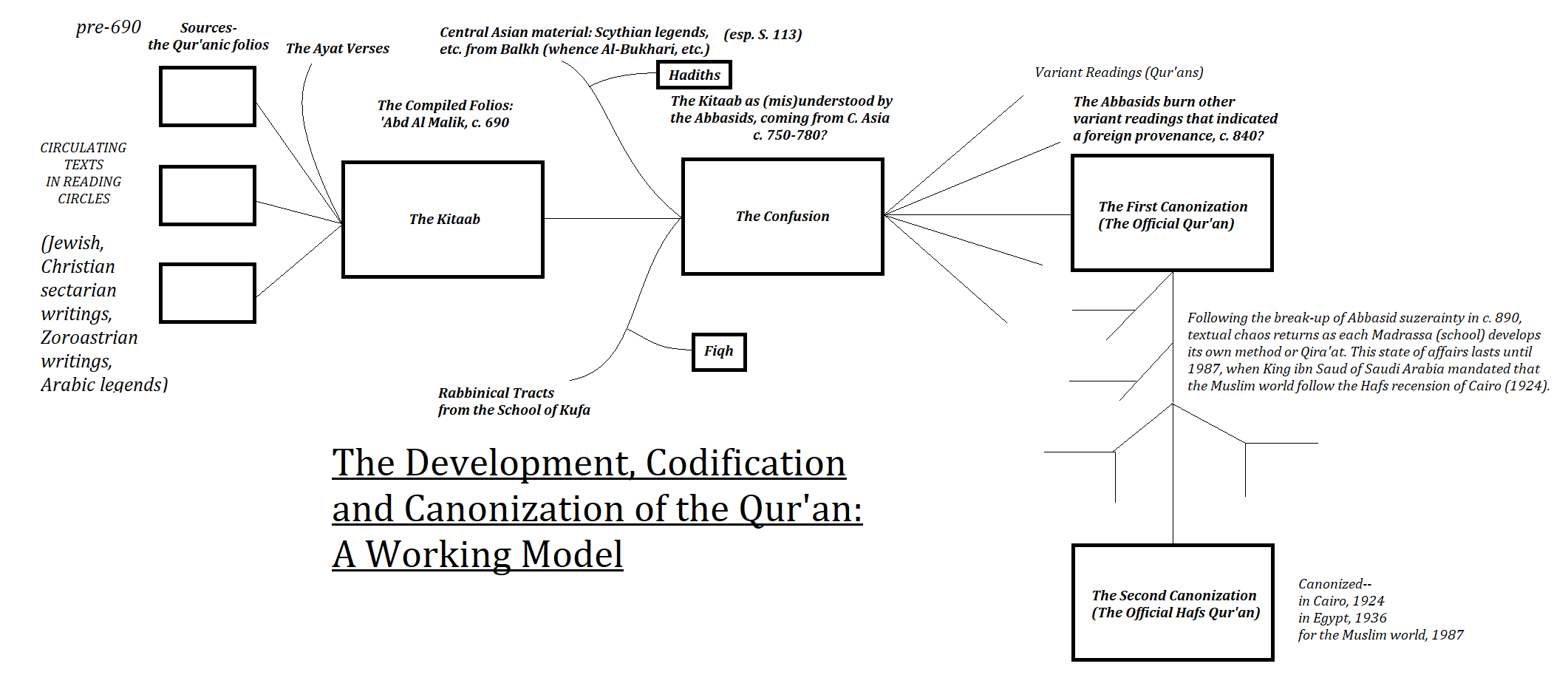

Fig. 1: A preview of the model. Edit: The quote for “The Second Canonization” should have the date 1985, not 1987.

Notes:

- See Islam Critiqued’s summary clip of it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d225z-Yn0vk.

- Unfortunately I cannot find the source of this quote but I will try to update it when I can.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fDuLG4IJG20&t=40s at 25:25.

- Hagarism, by Patricia Crone and Michael Cook. Cambridge University Press (Feb. 28 1980).

- The Syro Aramaic Reading of the Koran, by Christoph Luxenburg and The Hidden Origins of Islam: New Research into its Early History, eds. Karl-Heins Ohlig & Gerd R. Puin.

- Muhammad and the Believers, by Fred Donner.

- Death of a Prophet, by Stephen J. Shoemaker.

- Though he most definitely existed it is unclear if Muhammad would have been his original name rather than a title; see the work of Luxenberg (The Syro-Aramaic Reading) and more recently Sneaker’s Corner on Youtube.

- “I think that for you, too, not all your laws and commandments are in the Qur’an which Muhammad taught you; rather there are some which he taught you from the Qur’an, and some are in surat albaqrah and in gygy and in twrh. So also we, some commandments our Lord taught us, some the Holy Spirit uttered through the mouths of its servants the Apostles, and some [were made known to us] by means of teachers who directed and showed us the Way of Life and the Path of Light.” – Quoted in the entry on “Dialogue Between A Monk of Bet Hale and an Arab Notable”, http://www.christianorigins.com/islamrefs.html#johndamascus. (Dialogue, pp. 470-72.)

- Source: Islamic Awareness

https://www.islamic-awareness.org/history/islam/inscriptions/dotr, and see my future post on the Dome of the Rock inscriptions. - Probably a philo-Judaic autonomous Roman governor of Syria of Arab origin. The Tradition acknowledges him to be an early opponent of Muhammad. So it is possible that Muhammad, while part of the proto-Zionist revival movement among the Judaized Northern Arabs, still maintained a significant Christian and Persian following in Hira, was undercut by the governor’s pro-Jewish and (as a Roman official) anti-Persian leanings. It was suggested by Sneakers’ that Mu’awiya could have been a Roman Arab general who was rewarded with an important governorship post, suggesting he could have been part of the army which defeated Muhammad during his last battle in Palestine (cf. Shoemaker, Death of a Prophet).

Note the dates: Muhammad’s death, 635/6 AD/CE (according to Shoemaker’s reconstruction), and 640/1, the year Mu’awiya becomes Governor of Syria. I maintain that he was actually the last such Roman governor, rather than the first “Islamic” one, though he would have definitely been an Arab with Abrahamist/pro-Judaic leanings. Considering the government in Hira was a mixture of Judaic, Christianized and Persianized elements with a significant pro-Persian contingent it stands to reason that the Islamic traditions’ account of him being an early opponent of Muhammad is a vestige of this early rivalry, which later created the Sunni-Shi’a split. Mu’awiya would have acted both as an independent autonomous governor (something like Mohammed Ali of Egypt who became the autonomous Wali of Egypt during the Napoleonic Wars, firmly detaching it from Ottoman suzerainty) as well as an agent of Roman punitive expeditions.

The Emir of Hira, Muhammad’s immediate successor–representing the Christ to come, though he never came–ruled a small province in the now-independent Iraq, while Mu’awiya acted as an autonomous agent pursuing Roman imperial goals in the region.

There were local quarrels with heretics in the Vandal ruled territory of Africa dating from the late 500s, for example; the exhausted Roman army would have presumably granted him permission to “walk into” the region unopposed by Roman garrisons with a local mercenary force to suppress them. Though this is just speculation on my part, he may have even had the support of the Miaphysite Church in Egypt as the Islamic tradition recounts many favourable things about the contemporary Bishop of Alexandria, Cyrus–known in Arabic as Al-Mukawkis. That Mu’awiya was not even a Christian would not have bothered the Romans, as long as he was their loyal servant–they had no problem fighting the (Arian) Christian barbarians of Germania.

As for his conquests in Syria he would have continued this energy and also pursued vengeance of the defeat of Heraclius by the Persians and the Judeo-Christian Arabs of Muhammad. The region would have been completely devastated by 200 years of constant warfare between Rome and Persia, so the absence of any shift in the archaeological record can be explained by a relatively bloodless diplomatic takeover of the Roman province.

Like many of the local pseudo-emperors of the Crisis of the Third Century, such as the Palmyrene Empire before him, Mu’awiya declaring himself the first Caliph–usurping the title nominally reserved for the Messiah to come (e.g. Jesus Christ), angering the Hira party–is nothing new under the sun. Or in this case, under the desert sun. He was merely the last in a long line of Eastern warlords who took advantage of decaying Roman power in the region to pursue their own personal fortunes and ambitions. - This is incorrectly translated as religion as the concept of religion in the modern sense clearly didn’t exist during Abraham’s time according to the German linguists, Hidden Origins.

- 61.9 (my translation): He is the One Who has sent His Messenger, Abraham, with guidance and the True Law, that His may be above all other covenants, even though the idolaters hate it.

- 3.3 (my translation): He has sent down to you the Book, the Truth which confirms what was sent before–this He also revealed in the Torah and Gospel.

- The Qur’an and its Biblical Subtext, by Gabriel Said Reynolds.

- 3.7 (my translation): “He is the One Who revealed to you the Book; in it are clear Signs, some which form the glue which binds this Book, and others act general guidance.”