Taken from famous atheist philosopher John Searle’s book “Mind, Language And Society: Philosophy In The Real World”,

Taken from famous atheist philosopher John Searle’s book “Mind, Language And Society: Philosophy In The Real World”,

[…][W]hen we act or think or talk in the following sorts of ways we take a lot for granted: when we hammer a nail, or order a takeout meal from a restaurant, or conduct a lab experiment, or wonder where to go on vacation, we take the following for granted: there exists a real world that is totally independent of human beings and of what they think or say about it, and statements about objects and states of affairs in that world are true or false depending on whether things in the world really are the way we say they are. So, for example, if in pondering my vacation plans I wonder whether Greece is hotter in the summer than Italy, I simply take it for granted that there exists a real world containing places like Greece and Italy and that they have various temperatures. Furthermore, if I read in a travel book that the average summer temperature in Greece is hotter than in Italy, I know that what the book says will be true if and only if it really is hotter on average in the summer in Greece than in Italy. This is because I take it for granted that such statements are true only if there is something independent of the statement in virtue of which, or because of which, it is true.

[…]These two Background presuppositions have long histories and various famous names. The first, that there is a real world existing independently of us, I like to call “external realism.” “Realism,” because it asserts the existence of the real world, and “external” to distinguish it from other sorts of realism-for example, realism about mathematical objects (mathematical realism) or realism about ethical facts (ethical realism). The second view, that a statement is true if things in the world are the way the statement says they are, and false otherwise, is called “the correspondence theory of truth.” This theory comes in a lot of different versions, but the basic idea is that statements are true if they correspond to, or describe, or fit, how things really are in the world, and false if they do not.

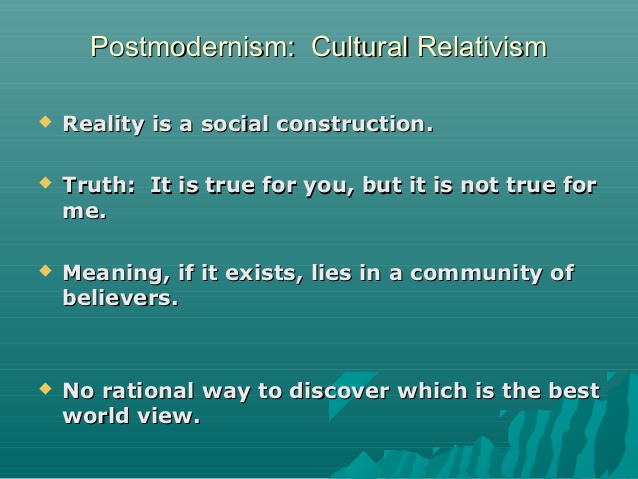

[…]Thinkers who wish to deny the correspondence theory of truth or the referential theory of thought and language typically find it embarrassing to have to concede external realism. Often they would rather not talk about it at all, or they have some more or less subtle reason for rejecting it. In fact, very few thinkers come right out and say that there is no such thing as a real world existing absolutely, objectively, and totally independently of us. Some do. Some come right out and say that the so-called real world is a “social construct.”

It is not easy to get a fix on what drives contemporary antirealism, but if we had to pick out a thread that runs through the wide variety of arguments, it would be what is sometimes called “perspectivism.” Perspectivism is the idea that our knowledge of reality is never “unmediated,” that it is always mediated by a point of view, by a particular set of predilections, or, worse yet by sinister political motives, such as an allegiance to a political group or ideology. And because we can never have unmediated knowledge of the world, then perhaps there is no real world, or perhaps it is useless to even talk about it, or perhaps it is not even interesting.

I have to confess, however, that I think there is a much deeper reason for the persistent appeal of all forms of antirealism, and this has become obvious in the twentieth century: it satisfies a basic urge to power. It just seems too disgusting, somehow, that we should have to be at the mercy of the “real world.” It seems too awful that our representations should have to be answerable to anything but us. This is why people who hold contemporary versions of antirealism and reject the correspondence theory of truth typically sneer at the opposing view.

[…]I don’t think it is the argument that is actually driving the impulse to deny realism. I think that as a matter of contemporary cultural and intellectual history, the attacks on realism are not driven by arguments, because the arguments are more or less obviously feeble, for reasons I will explain in detail in a moment. Rather, as I suggested earlier, the motivation for denying realism is a kind of will to power, and it manifests itself in a number of ways. In universities, most notably in various humanities disciplines, it is assumed that, if there is no real world, then science is on the same footing as the humanities. They both deal with social constructs, not with independent realities. From this assumption, forms of postmodernism, deconstruction, and so on, are easily developed, having been completely turned loose from the tiresome moorings and constraints of having to confront the real world. If the real world is just an invention-a social construct designed to oppress the marginalized elements of society-then let’s get rid of the real world and construct the world we want. That, I think, is the real driving psychological force behind antirealism at the end of the twentieth century.

Comment from Wintery Knight: https://winteryknight.com/2020/07/08/the-psychological-motivation-of-those-who-embrace-postmodernism-6/

People, from the Fall, have had the desire to step into the place of God. It’s true that we creatures exist in a universe created and designed by God. But, there is a way to work around the fact that God made the universe and the laws that the universe runs on, including logic, mathematics and natural laws. And that way is to deny logic, mathematics and natural laws. Postmodernists simply deny that there is any way to construct rational arguments and support the premises with evidence from the real world. That way, they imagine, they are free to escape a God-designed world, including a God-designed specification for how they ought to live. The postmoderns deny the reliable methods of knowing about the God-created reality because logic and evidence can be used to point to God’s existence, God’s character, and God’s actions in history.

And that’s why there is this effort to make reality “optional” and perspectival. Everyone can be their own God, and escape any accountability to the real God – the God who is easily discovered through the use of logic and evidence. I believe that this is also behind the rise of atheists, who feign allegiance to logic and science, but then express “skepticism” about the origin of the universe, the fine-tuning of the universe, objective morality, the minimal facts concerning the historical Jesus, and other undeniables.