Richard Cooks. Taken from here.

In The Master and His Emissary, Iain McGilchrist writes that a creature like a bird needs two types of consciousness simultaneously. It needs to be able to focus on something specific, such as pecking at food, while it also needs to keep an eye out for predators which requires a more general awareness of environment.

These are quite different activities. The Left Hemisphere (LH) is adapted for a narrow focus. The Right Hemisphere (RH) for the broad. The brains of human beings have the same division of function.

The LH governs the right side of the body, the RH, the left side. With birds, the left eye (RH) looks for predators, the right eye (LH) focuses on food and specifics. Since danger can take many forms and is unpredictable, the RH has to be very open-minded.

The LH is for narrow focus, the explicit, the familiar, the literal, tools, mechanism/machines and the man-made. The broad focus of the RH is necessarily more vague and intuitive and handles the anomalous, novel, metaphorical, the living and organic. The LH is high resolution but narrow, the RH low resolution but broad.

Dido Building Carthage – William Turner

The LH exhibits unrealistic optimism and self-belief. The RH has a tendency towards depression and is much more realistic about a person’s own abilities. LH has trouble following narratives because it has a poor sense of “wholes.” In art it favors flatness, abstract and conceptual art, black and white rather than color, simple geometric shapes and multiple perspectives all shoved together, e.g., cubism. Particularly RH paintings emphasize vistas with great depth of field and thus space and time,[1] emotion, figurative painting and scenes related to the life world. In music, LH likes simple, repetitive rhythms. The RH favors melody, harmony and complex rhythms.

A Muse – Pablo Picasso

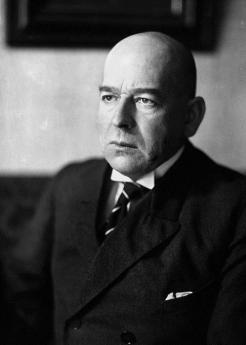

One reason children’s art is typically so bad is that children and many adult non-artists tend to draw what they “know” (LH) rather than what they perceive (RH). The following picture of two tables illustrates the difference:

The non-artist knows the table is rectangular and so a rectangle is drawn with a couple of legs sticking out. The picture on the right is closer to what is actually seen.

It usually takes a lot of training and practice to draw or paint something resembling what is really experienced. The default is LH ugliness and two-dimensional flatness. Good figurative painting requires a sense of space and depth. Concerning colors, the LH tendency when attempting to paint a black velvet dress, for instance, would be to grab a tube of paint black paint and to apply it. The LH “knows” the dress is black. In reality, even black velvet dresses are made up of multiple shades of color. They are not black holes after all.

The LH picture of a table and the RH table make an excellent visual metaphor for the frequent crudity of LH theory and unreal abstract concept-driven thinking. Homo economicus, the perfectly rational and egoistic consumer invented by bad economists, or the notion that all human psychology is hedonistic and driven only by pleasure, or brains are information processing devices, are examples of the gross LH simplifications and distortions that actually make human behavior harder to understand and predict, and more, not less, inexplicable.

Patients with RH strokes, now dependent on their LH, tend to feel that their paralyzed left sides of their bodies do not belong to them. Patients have been known to throw their own (left) arm out of bed because they are convinced the arm is not theirs. Of course, they tend to throw the rest of themselves out of bed in the process. Patients with LH strokes are not similarly divorced from reality.

People dependent on the LH tend to be averse to accepting responsibility. The paralyzed portion of the body has nothing to do with them, they think. In one experiment a doctor injected saline solution into a patient’s paralyzed arm and told the patient the arm was now paralyzed as a result. Once the LH patient could blame someone else for the paralysis she was happy to acknowledge that the paralyzed arm was her own.

Schizophrenia is a disease of extreme LH emphasis. Since empathy is RH and the ability to notice emotional nuance facially, vocally and bodily expressed, schizophrenics tend to be paranoid and are often convinced that the real people they know have been replaced by robotic imposters. This is at least partly because they lose the ability to intuit what other people are thinking and feeling – hence they seem robotic and suspicious.

Oswald Spengler

Oswald Spengler’s The Decline of the West as well as McGilchrist characterize the West as awash in phenomena associated with an extreme LH emphasis. Spengler argues that Western civilization was originally much more RH (to use McGilchrist’s categories) and that all its most significant artistic (in the broadest sense) achievements were triumphs of RH accentuation.

The RH is where novel experiences and the anomalous are processed and where mathematical, and other, problems are solved. The RH is involved with the natural, the unfamiliar, the unique, emotions, the embodied, music, humor, understanding intonation and emotional nuance of speech, the metaphorical, nuance, and social relations. It has very little speech, but the RH is necessary for processing all the nonlinguistic aspects of speaking, including body language. Understanding what someone means by vocal inflection and facial expressions is an intuitive RH process rather than explicit.

Though communication exists between the two hemispheres, there is a fairly high degree of independence and needs to be. Awareness of context or extraneous background sounds can interfere with focus. Getting lost in specifics can harm a sense of the big picture. Making RH intuitive processes explicit can actually harm, slow them down or even destroy them. A joke explained is no longer funny. A metaphor spelled out can no longer function. The gestural aspect of speech (RH) if made conscious is merely distracting. Self-consciousness (LH) interferes with “flow” and public speaking. Processes like going to sleep involve letting go. We fall asleep, but wake up, having control over, rising above your feelings. Having a name on the tip of your tongue is more likely to be recalled if you stop focusing on it. Shortly before executing a jump in figure skating, breaking a board in karate, shooting at a target, thinking must cease. Happiness is best achieved indirectly not explicitly.

RH is very much the center of lived experience; of the life world with all its depth and richness. The RH is “the master” from the title of McGilchrist’s book. The LH ought to be no more than the emissary; the valued servant of the RH. However, in the last few centuries, the LH, which has tyrannical tendencies, has tried to become the master. The LH is where the ego is predominantly located. In split brain patients where the LH and the RH are surgically divided (this is done sometimes in the case of epileptic patients) one hand will sometimes fight with the other. In one man’s case, one hand would reach out to hug his wife while the other pushed her away. One hand reached for one shirt, the other another shirt. Or a patient will be driving a car and one hand will try to turn the steering wheel in the opposite direction. In these cases, the “naughty” hand is usually the left hand (RH), while the patient tends to identify herself with the right hand governed by the LH. The two hemispheres have quite different personalities.

The connection between LH and ego can also be seen in the fact that the LH is competitive, contentious, and agonistic. It wants to win. It is the part of you that hates to lose arguments.

Using the metaphor of Mystery and Order, the RH deals with Mystery – the unknown, the unfamiliar, the implicit, the emotional, the dark, danger, the chaotic. The LH is connected with Order – the known, the familiar, the rule-driven, the explicit, and light of day. Learning something means to take something unfamiliar and making it familiar. Since the RH deals with the novel, it is the problem-solving part. Once understood, the results are dealt with by the LH. When learning a new piece on the piano, the RH is involved. Once mastered, the result becomes a LH affair. The muscle memory developed by repetition is processed by the LH. If errors are made, the activity returns to the RH to figure out what went wrong; the activity is repeated until the correct muscle memory is developed in which case it becomes part of the familiar LH.

Science is an attempt to find Order. It would not be necessary if people lived in an entirely orderly, explicit, known world. The lived context of science implies Mystery. Theories are reductive and simplifying and help to pick out salient features of a phenomenon. They are always partial truths, though some are more partial than others. The alternative to a certain level of reductionism or partialness would be to simply reproduce the world which of course would be both impossible and unproductive. The test for whether a theory is sufficiently non-partial is whether it is fit for purpose and whether it contributes to human flourishing.

The LH looks for and finds order in the flux of experience. In reality, every person is slightly different and every experience is unique. The 100th time something is done is different from the 99th. In order not to just get lost in Mystery, the LH uses categories and applies them across experience. While focusing on the repetitive aspects of experience can be useful, too much LH and Order is boring – resulting in the feeling “been there, done that.”

Analytic philosophers pride themselves on trying to do away with vagueness. To do so, they tend to jettison context which cannot be brought into fine focus. However, in order to understand things and discern their meaning, it is necessary to have the big picture, the overview, as well as the details. There is no point in having details if the subject does not know what they are details of. Such philosophers also tend to leave themselves out of the picture even when what they are thinking about has reflexive implications. John Locke, for instance, tried to banish the RH from reality. All phenomena having to do with subjective experience he deemed unreal and once remarked about metaphors, a RH phenomenon, that they are “perfect cheats.” Analytic philosophers tend to check the logic of the words on the page and not to think about what those words might say about them. The trick is for them to recognize that they and their theories, which exist in minds, are part of reality too.

The RH test for whether someone actually believes something can be found by examining his actions. If he finds that he must regard his own actions as free, and, in order to get along with other people, must also attribute free will to them and treat them as free agents, then he effectively believes in free will – no matter his LH theoretical commitments.

By trying to emulate the explicit formulations of science, analytic philosophy effectively excludes from its purview and thus from its conception of reality, all RH phenomena. By focusing only on what can be made explicit and what can be put into words using them literally, they distort reality. This happens even in their discussion of consciousness.

The philosopher Martin Heidegger tried to describe the human condition, how humans are in the world, in a more RH way. He invented the term “Dasein,” which is described as Being-in-the-world.[2] We have a dim apprehension of the situations or contexts in which activities are undertaken. We are building a house, meeting a friend, sick of our lives, bored, relaxed, anxious, etc.. Each RH feeling or purpose reveals the world in different ways, foregrounding some things out of the infinite complexity of background. The RH determines what the LH sees. One person experiences X as a friend, another as a son, another as a student, another as a mechanic. Each experience is legitimate and none is comprehensive.

Martin Heidegger

Heidegger described people as always, already in the world. The World is the largest conception one might have of context. It is pre-theoretical and implicit. We find ourselves in the world and then try to make sense of it. We are in the world and then proceed to have theories about it. We do not and cannot prove the external world exists as a theoretical matter.

Most of our interaction with the world is precognitive. When we learn a skill (anomalous at the time it is learned) we have to learn it consciously (RH). Once acquired, the skill becomes LH – the known, the familiar, the routine. Colin Wilson calls this “the robot.” By that he means all activities that can be undertaken without the necessity of conscious thought, such as driving a car in non-difficult conditions. Driving a car is not entirely unconscious, but neither is it very conscious.

We demonstrate that we know what a hammer is, what it means, by stretching out a hand and hammering with it. Only if it breaks do we look at it and think about it. The hammer is “ready-at-hand,” and then “present-at-hand” if it breaks.

From a RH perspective, to understand a hammer is to understand what it means; its function. Since meaning is a matter of connections to context, the thing to be studied must be carefully placed in its appropriate context rather than being studied in isolation. Just analyzing the wood and metal used to construct the hammer, which would be a LH approach, is not to understand its meaning. The exact materials, so long as they are fit for purpose, do not really matter.

To understand the hammer it is necessary to look at in relation to the tool users who employ it, then to recognize that it points to nails and boards and then to the items constructed out of them. These matters of context are understood dimly via the RH and not at all by the LH. The ultimate meaning might be to build a house; to provide shelter for people.

Dasein is in the world concernfully. How the world is going for it, matters to Dasein. Dasein is not an object to be fully seen and understood. It reaches into the past and imagines alternative futures. It is a clearing in the forest where things get revealed. It is also “Being-toward-death.”

For Aristotle, passive nous (mind) is the great sweep of perceptions cascading over us. Active nous (LH) involves focusing on some elements and not others, partly to avoid confusion and partly to avoid sensory overload. We do not want to be constantly thinking about persistent but unimportant sensations like the feel of the shirt on our backs, etc..

Attempting to understand consciousness by focusing only on the LH will omit everything connected to the RH. All such accounts tend to say nothing about music, humor, intuition, context, the metaphorical, emotion, emotional nuance of language, the unique and individual, social connection, and meaning.

Having a stroke in the RH means having to make do with the LH. Without the ability to deal with gestalts, the LH is forced to identify a person by single attributes, like a nose, or mouth, or haircut. Normal people recognize someone using the RH which has a broader focus and can see wholes. RH also deals with the unique – which is necessary to tell one person from another. RH perception takes multiple factors into account, including how a person moves. It provides fewer details, but it can see the forest for the trees.

LH accounts of consciousness tend only to include what can be seen by the LH. Unless a person is autistic, these accounts will therefore not correspond very well to our actual experience of consciousness. They will be exceedingly partial and incomplete, focusing only on what is explicit and can be articulated clearly.

A lot of moving through the world is non-linguistic. Animals reason and problem-solve non-linguistically and we do too, much of the time.

It is possible in experiments to cause each hemisphere in turn to cease to function using magnetism – brains are electro-magnetic at some level and this can be manipulated. In one experiment, subjects were given the following syllogism:

All monkeys climb trees.

Porcupines are monkeys.

Therefore, porcupines climb trees.[3]

When the RH is functioning subjects reject the argument as unsound since the second premise is false. The argument is recognized as technically valid – the premises if true would guarantee the truth of the conclusion – but that is all.

When only the LH was working, subjects accepted the argument as legitimate. When asked – but what about the second premise?, subjects acknowledged that it was false, but accepted it anyway saying “but it says here…”

The LH tends to accept a coherence theory of truth and knowledge – do beliefs create a self-consistent system? The RH embraces a correspondence theory of truth and knowledge – do beliefs actually match reality? (lived experience). Since we tend to move in social circles that are not simply random cross-sections of society generalizations based in RH experience sometimes need to be corrected by LH empirically gathered data. On the other hand, LH theory can be heavily ideologically driven, such as ideas about men and women, that are contradicted by actual experience. That’s when the coherence theory of truth is so dangerous because it is immune to correction.

The trouble with system-creation is that intellectual systems try to provide an answer for everything. This is a power-grab by the LH – making theory primary and comprehensive. It effectively claims omniscience via self-referential abstractions. Reality, however, includes a high degree of flux and process. Heraclitus’ aphorisms capture this well. “It is not possible to step into the same river twice,” he wrote. This is because man is in a constant state of change and with its flowing water, so is the river. There is a Logos that provides order to things so that things are not merely chaotic, but that order is better captured by the metaphor of the organic and the organic is wet, flexible, goal-directed, growing and changing. And it is the RH that deals with living things.

Heraclitus

In the past, the universe and the world were thought of as alive and ensouled. The word “cosmos” refers to a harmonious well-ordered whole which has pleasant home-like connotations. The tendency since the scientific revolution has been to substitute the organic metaphor for the mechanical and metaphors tend to determine what is perceived.[4]

A LH mode of thought concerning free will or the existence of telepathy might be to reject them both on the grounds that – “I don’t see how that is possible,” i.e., they might seem to contradict the thinker’s materialistic metaphysics. The RH response is to focus on the actual evidence and let the data determine the theory. The appropriate modus operandi is to start with RH perception, perhaps modify those perceptions after pondering them (LH), and then return to RH experience.

For instance, someone is looking into the distance. Another person comments that the lights are beautiful. The first person alters his attention and focus slightly and he notices the beauty of the lights. Beauty is perceived but perception can be modified by thought. Likewise little children and even some animals perceive injustice (RH) at least when it concerns themselves. This perception can be modified by thought and theory (LH) – not always for the better. The result can be a permanent alteration in perception. However, attempts to generate morality through moral theories like utilitarianism do not work. The LH is analytic, not generative.

We do not know the origin of life. We do not know how or even if consciousness can emerge from matter. We do not know the nature of 96% of the matter of the universe. Clearly all these things exist. They can provide the subject matter of theories but they continue to exist as theorizing ceases or theories change. Not knowing how something is possible is irrelevant to its actual existence. An inability to explain something is ultimately neither here nor there.

If thought begins and ends with the LH, then thinking has no content – content being provided by experience (RH), and skepticism and nihilism ensue. The LH spins its wheels self-referentially, never referring back to experience. Theory assumes such primacy that it will simply outlaw experiences and data inconsistent with it; a profoundly wrong-headed approach.

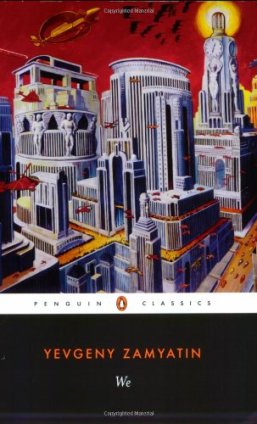

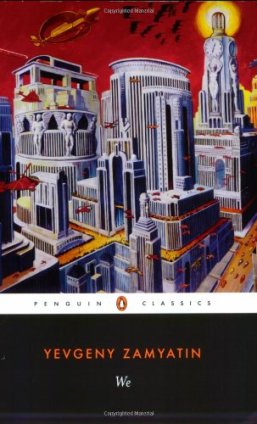

Zamyatin, Gödel, Turing and Keats

Gödel’s Theorem proves that not everything true can be proven to be true. This means there is an ineradicable role for faith, hope and intuition in every moderately complex human intellectual endeavor. There is no one set of consistent axioms from which all other truths can be derived.

Gödel and Einstein

Alan Turing’s proof of the halting problem proves that there is no effective procedure for finding effective procedures. Without a mechanical decision procedure, (LH), when it comes to moderately complex matters, intuition and insight will be required. (RH)

Axioms must retain a tentative, provisional, hypothetical nature ready to be discarded if they are contradicted by further evidence.

What is very significant about Gödel and Turing is that they provide certainty about the irreducible nature of uncertainty. In other words, they provide definitive proof once and for all of the limitations of LH thinking. They demonstrate to what should be to the satisfaction of even the most die-hard LH rationalistic reductionist and skeptic that the RH cannot be dispensed with. It is simply not possible have everything in the clear light of day; dry, proven, known, and nailed down. Thinking is not merely computation.

Intuition, the context of lived experience, being always already in the world, emotion, metaphor, humor, irony, and all the other things associated with the right hemisphere of the human brain are here to stay. The left hemisphere’s love of logic, mechanism, clarity and certainty must be tempered by the right hemisphere’s tolerance for ambiguity, uncertainty, and the organic. The fantasy of an omniscient science should be extinct.

A liberating character in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We, chastising the benighted LH dominated mathematician in a horrible LH culture, says “Oh come on – knowledge! This knowledge of yours is utter cowardice. Yes, that’s it – really. You just want to build a little wall around infinity – and you’re afraid to look behind it.”[5] The One State tames a wild zigzag into a straight line – “a great, divine, precise, wise, straight line – the wisest of lines.” The result of “integrating the grand equation of the universe.”[6] The main character, D-503, writes: “I personally do not see anything beautiful in flowers and the same goes for everything that belongs to the wild world…Only the rational and the useful are beautiful: machines, boots, formulas, food, etc..”[7] Zamyatin demonstrates an exact understanding of the LH attitude and its limitations.

The LH has a tendency to turn the known world; the comprehensible, into the world; outlawing the transcendent and infinite – that, as D-503 writes, which is incapable of being encompassed by an equation.

John Keats

The Romantic poet John Keats became frustrated by fellow poet Samuel Coleridge’s desire for definitive answers and wrote in a letter to his brothers, George and Thomas;

Several things dovetailed in my mind, and at once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously — I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason — Coleridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half knowledge. This pursued through Volumes would perhaps take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.

Facts are in a sense dead. Facts exist in the clear light of day. They are in the realm of Order which represents the familiar, the known, the robotic, and thus, the boring.

The point of intensest life and interest occurs at the dividing line between Mystery and Order. Creativity and discovery, philosophical, scientific and artistic, emerge from a state of wonder; neither being overwhelmed by infinity and the darkness of Mystery which would be fatal, nor insisting on the certainty of facts already known of Order. Scientific discoveries tend to come by accident. A scientist asks a question and in the process of trying to answer it, answers another question. Since practitioners do and theoreticians write, the role of theory and reason gets exaggerated in histories of discovery. Most scientific advances come through chance, and trial and error. Trial and error involve Keats’ description of negative capability. The experimenter can have tentative hypotheses or intuitions but if he imagines that he already knows the outcome or insists on particular and foreordained results his research ceases.

Creativity has a tentative quality with no guaranteed outcome. There is an understandable desire to find the formula for creativity – rote instructions for writing the perfect novel might seem nice – but formulas and rote instructions are the opposite of creativity. Certainty and creativity are simply incompatible. There can be no creation machine. Creativity is more aligned with the organic, living, and “wet.” It is permeated by mystery and the dark.

“Data” from Star Trek Next Generation

It is hard not to fantasize about a Star Trek Next Generation future where all drugs, for instance, will be designer drugs and scientific discovery loses its haphazard guesswork and tentativeness.[8] Just one or two designer drugs, AZT being the prime example, have ever been created. The metaphor of Mystery and Order demonstrates why this will never change. Such “directed” research rests too heavily on what is already known or thought to be known; leaving no room for what is not already understood.

Jet engines, for instance, were developed by tinkering. The theory of how they work came later.

How to kill a research program

The following indicative story is from chapter four of John Gall’s The Systems Bible.[9] The story is fictional, but the scenario is all too familiar. It demonstrates how LH desires for clarity and explicitness in the name of accountability and efficiency, and the creation of complex systems can actually neutralize and ruin research programs.

Gall imagines Lionel Trillium, a shy young man whose questions about human reproduction went unanswered as a child and who developed instead an interest in the reproductive cycle of plants. He has been a moderately successful junior professor of biology with ongoing research programs.

His head of department, Baneberry, on the other hand, has been unproductive for years. He picks up a book about management and is struck with excitement. He will reorganize his department in a way calculated to boost productivity and efficiency. The administration greets this idea with enthusiasm. The plan is to get the other members of the department to write down their research objectives for the year. Their success or failure will then be judged according to the criteria that the faculty members themselves have provided. Baneberry will be able to hold them to account for any difference between what they said they were going to do and what they actually did.

A side effect of this approach is that any research that does not match the stated research objectives will be counted as a failure and the professor will get no credit for it.

The news of this new policy horrifies Lionel and has a depressing effect. If Lionel were going to write anything down about his Goals and Objectives it would be “I love botany. Let me keep studying it.” However, this is clearly unacceptable.

John Gall

The results of science might be nicely clear, logical and explicit but the method of reaching these results necessarily involves delving into the unknown and mysterious. Generating hypotheses to be tested is a matter of imagination, intuition informed by experience and creativity. One is reaching into the realm of Mystery – what is currently unknown – and trying to find a hitherto undiscovered Order. To do that, inspiration and insight are required.

Inspiration and insight are likely to be the product of enthusiasm and interest. In fact, many seemingly intractable problems in various fields are solved by someone with no vested interest in the field; just a passing, but genuine curiosity.

Productive creativity in any area is likely to be a combination of expertise, skills, prior knowledge and crucially, a temporary enthusiasm. By definition, temporary enthusiasms do not last. So it is important that a thinker pursues the interest while it exists and is at its keenest. Enthusiasm provides the needed grit not to stop as soon as things get difficult, promotes a joyful attitude and bolsters effort. Boredom and frustration are unlikely to help, whereas a certain relaxed playfulness might well assist.

There are inevitably some boring aspects to mastering something. The goal-driven nature of temporary enthusiasms means that these elements are likely to be better tolerated; simply subsumed within the larger sense of purpose.

It is the very nature of research that it is not possible to list Goals and Objectives in advance. Or rather, one might have Goals and Objectives but they must be provisional and change as research progresses. If the outcome of research were known in advance no research would be necessary. By definition, what one will discover is a mystery.

Since temporary enthusiasms are not predictable or possible to artificially generate, nor to know in advance what one will find, it is not possible to know what direction research will go in. There is simply no point in forcing someone to think about a problem that he has no interest in; not if the goal is to be creative.

Inspiration, creativity and temporary enthusiasms are killed by trying to systematize them. A system is akin to bureaucracy and in this case it is supposed to promote productivity and efficiency. Ironically, such a system is guaranteed to do the opposite and this is the case with nearly all systems. Systems are LH affairs.

A system is akin to an algorithm – a set procedure for producing predictable results. Systems arise in response to problems. There are several problems with this. One is that the problem the system is designed to remedy may not be the problem at hand. Another issue is that any problem the system cannot “see” is typically deemed not to exist. And finally complex systems produce unpredictable new problems of their own – often in exact opposition to the stated goal of the system.

If authors and musicians were forced to follow systems the results would be predictably awful, and it is the same for scientists.

This is not the same as setting certain times of day aside for attempts at productive effort. There is nothing wrong with being organized – in fact, that will be very helpful. Writing music or novels in the morning hours, for instance, might be a very good idea. But no algorithm exists to guarantee the result. Algorithms are also known as “mechanical decision procedures” and they are literally a mechanical, rule-governed step-by-step method for achieving specific results. E.g., long division. They are tools, but they are no more creative than the chisel of a sculptor, although the chisel in this case is a crucial instrument for the creative process.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) takes nearly every productive scientist interested in cancer research and inserts them into a giant bureaucracy crammed filled with rules and regulations, research grant applications, Goals and Objectives, and effectively neutralizes these scientists by killing any spontaneity, such as temporary enthusiasms and unpredictable results. Research projects will have to be approved by committees and then funding for that goal and only that goal will be provided. Famously, the NIH tested 40,000 substances to see if they had any cancer fighting properties. None did. Zero. The amount of time and money wasted on this enterprise was stupefying. A machine-like uninspired mindless approach simply failed.

One reason that research in the private sphere is much more productive than government funded R & D is that companies are interested in making money. They are less filled with layers and layers of bureaucracy each one being accountable to the next. Viagra was discovered during research into blood pressure medicine. Erections were an unexpected side effect and initially treated as a problem. By remaining flexible and open-minded and not locked into stated Goals and Objectives, the company decided this side-effect could actually be the new product and Viagra was born. This kind of happy accident is actually the norm.

Lionel Trillium is in the impossible situation of trying to guess what he will be interested in in the future. He desperately does not want to write anything down. By getting Lionel to write down his Goals and Objectives, Baneberry is actually neutralizing Lionel and ensuring that only a pitiful trickle of probably uninspired research will result.

If the rather timorous Lionel dares try to complain to Baneberry or Baneberry’s superiors, Baneberry can respond that he, Baneberry, did not decide on the Goals and Objectives. It was Lionel himself who proposed them so Lionel has no right to complain. Lionel is not being forced to do anything that he did not want to do. Except this is a lie. Lionel was compelled to predict a future that is unpredictable and then compelled again to abide by what he wrote.

The European Union provides money for research and development. Scientists are supposed to outline research programs projected two years into the future. An engineer friend of mine told me that he would be asked to apply for such grants and then had to try to retrofit what he actually discovered or invented to what he said he was going to do. He now refuses to apply. Government funded R & D is immensely counterproductive for this reason; particularly because it tends to target previously successful scientists – the ones that had been doing just fine without government grants – and shut them down.

None of this contradicts the notion that innovation is 99% perspiration, 1% inspiration. Enthusiasm means someone is self-motivated and likely to work harder than could reasonably be expected by a supervisor. Supervision is expensive – supervisors are usually paid more than the people of whom they are in charge. A self-reliant employee is a cheaper and more productive one. A lot of hard work mastering aspects of a field of study is usually going to be required for any breakthrough of insight. However, when it comes to creativity, mere effort is insufficient. Scientists must come up with hypotheses to test and there is no algorithm for that.

Dan Ariely

Dan Ariely, who is particularly good at asking questions and then devising experimental methods for answering them, proved this in a series of experiments outlined in The Upside of Irrationality. He found that offering incentives such as paying someone more for an activity works best when the work being done is mechanical and involves sheer physical effort. If someone is asked to do as many jumping jacks as he can in one minute, paying him a hundred dollars might mean he squeezes out a couple more. If, however, someone is asked to paint a beautiful picture for one thousand dollars and then after it is completed, two thousand dollars is offered for a more beautiful picture, the chances are the artist will be unable to comply. Or, imagine a particular form of surgery has a 4% chance of complications – will paying the surgeon five million dollars above his usual fee for a successful outcome lower that percentage? Might his hands begin to shake, his forehead perspire and similarly unproductive things result? Would he not already being doing his best? Will asking someone to solve a puzzle faster by paying him more be likely to work? Unlike physical effort, these things are not directly in someone’s control. That is why paying a child to read a book makes more sense than paying him to get an “A” on an assignment, although such payments might have other unintended negative consequences.

[1] Oswald Spengler makes a connection between visual depth of field; space, and the spiritual and transcendent. Mystical experience is RH, as is experience in general. LH analysis can help make sense of the experience or parse its meaning, but there is a reason that excessive rationalism and the atheistic tend to go together.

[2] Calling Dasein “the human,” is misleading because it reduces what it is to be to biological terms. A human being is just one very limited way of referring to Dasein.

[3] The Russians who did this experiment did not know that some kinds of porcupines really do climb trees, so it is necessary to ignore this inconvenient fact!

[4] Interestingly, women scientists tend to gravitate to the living and organic; inclined to major in biology and veterinary science rather than physics.

[5] Zamyatin, Yevgeny, We, Modern Library, 2006, p. 37.

[6] Zamyatin, Yevgeny, We, Modern Library, 2006, p. 4.

[7] Ibid, p. 44.

[8]Although STNG contains elements of Order, the Enterprises’ mission is explicitly exploratory. The drama of the stories exists only through encountering the unknown and unexpected with the constant threat of annihilation. The figure of the android “Data” also centers around the mystery of what it is to be human.

[9] General Semantics Press, 2002.

How familiar are you with the original research behind the claims of LH/RH brain activity emphasis and personality differences?

It’s my understanding that they’re based on shoddy data and execrable methodology and have never managed to be replicated, but I admit freely it’s not my field.

Re: Rhetocrates: My understanding is that is not true. There was at one point some fluffy New Agey garbage on the topic, I think. But that situation has been rectified. Regardless of the biology, the different approaches to thinking and attitudes to life I am painfully aware of having multiple degrees in philosophy – one BA, two MAs and a PhD. I can confirm that what is being referred to as “LH” is a very real phenomenon, whether it turns out to be LH or not – unfortunately! My preference would be that it would be only the result of a fevered imagination! If you read the novel “We” you can get an idea of the flavor of autistic style thinking if you are lucky enough to be unfamiliar with it. Lucky you if you are.

Odd that I’m left-handed but also seem to be one of the most “left hemisphere” of the Orthosphere writers. When I was a kid, I heard that left-handers were supposed to be creative but bad at math. (As you point out in your article, mathematics is itself a very creative enterprise, but this was not widely appreciated. Presumably they meant that lefties are bad at calculating.) I absolutely love math but admit that I’m not especially good at it; I’m still waiting for my creativity to manifest itself. I suppose it’s possible that the hemisphere that dominates in cognitive areas may not be the one that dominates in motor areas.

Let’s take a poll. Any other lefties here?

Hi, Bonald: There is a good chance that your brain is organized the same as us righties or that it is just inverted (sideways, not upside down!). From “The Master and His Emissary:

In the 11 per cent, who are broadly left-handed, there will be

variable conformations, which logically must follow one of three patterns:

the standard pattern, a simple inversion of the standard pattern, or some

rearrangement. The majority (about 75 per cent) of this 11 per cent still

have their speech centres in the left hemisphere, and would appear to

follow broadly the standard pattern. It is, therefore, only about 5 per cent

of the population overall who are known not to lateralise for speech in the

left hemisphere. Of these some might have a simple inversion of the

hemispheres, with everything that normally happens in the right

hemisphere happening in the left, and vice versa; there is little significance

in this, from the point of view of this book, except that throughout one would

have to read ‘right’ for ‘left’, and ‘left’ for ‘right’. It is only the third group who,

it has been posited, may be truly different in their cerebral organisation: a

subset of left-handers, as well as some people with other conditions,

irrespective of handedness, such as, probably, schizophrenia and

dyslexia, and possibly conditions such as schizotypy, some forms of

autism, Asperger’s syndrome and some ‘savant’ conditions, who may have

a partial inversion of the standard pattern, leading to brain functions being

lateralised in unconventional combinations. For them the normal

partitioning of functions breaks down.

I’m not a lefty, but I’ve noticed that among the best engineers I’ve been acquainted with, a disproportionate number are lefties.

@Ian: That’s interesting!

On this general topic, I just found this highly amusing article:

https://www.chronicle.com/article/Design-Thinking-Is-a/243472?cid=wsinglestory_41_1

Stanford has bought into a cult that claims to give students a recipe for being “innovative”.

“Innovative” and “unique” are favorite words of corporate kakobabble.

Richard: Concerning your invocation of Oswald Spengler…

In The Decline, Vol. II in the chapter on “Peoples, Races, and Tongues” (which I happen currently to be re-reading for the nth time), Spengler, as elsewhere, distinguishes between the “cosmic-plantlike side of life,” the “destiny [of which] is determined by… the bodily succession of parents and children, the bond of the blood,” and the “tendency to take root in a landscape,” from “waking -consciousness,” which expresses itself in language, such that there are “currents of being and linkages of waking-being.” The first, the “cosmic-plantlike side of life,” resembles Edmund Husserl’s Lebenswelt and Heidegger’s Dasein. It is the pre-given, the background-environment, against which, and only against which, the subject becomes aware of itself as, precisely, a thematic self-consciousness. The second, the “waking-consciousness,” would correspond to Heidegger’s “thrownness,” and it expresses itself, Spengler writes, through propositional language. From the parent-child succession and from living for generations in a particular place, arises “Race,” which is nearly synonymous with Lebenswelt or Dasein in Spengler’s usage. Spengler writes: “Race is something cosmic and psychic (Seelenhaft), periodic in some obscure way, and in its inner nature partly conditioned by major astronomical relations.” But “waking-consciousness,” on the other hand, expressing itself through the prescriptions of language, partakes in “causal forms,” that is, in syntax, grammar, and correct idiom. “To Race,” writes the Munich realist, “belong the deepest meanings of the words ‘time’ and ‘yearning’; to language those of the words ‘space’ and ‘fear.’”

Spengler’s “cosmic-plantlike” seems to me to correspond with what your essay calls the Right Brain; his “waking-consciousness” with what your essay calls the Left Brain. Or at any rate the Right Brain is the organ — or faculty — that attunes the subject cosmically, and the Left Brain is the organ — or — faculty that puts the ego in rational communication with other egos.

I could easily find other passages in The Decline apposite to your topic, especially in Vol. I, in the first three chapters, but the items that I quote above give the flavor of Spengler’s anticipation of the Right-Brain/Left-Brain idea.

Profoundly interesting read. This idea of how the brain has evolved its two hemispheres to cope with the reality (or meta-reality) of chaos and order in the world is a fascinating concept.

Thanks, Nicolas Helssen. I should give credit, of course, to Iain McGilchrist and a bit to Jordan Peterson. But McGilchrist’s work, I find articulates some of the issues I had with my degrees in philosophy. I always had a sympathy and intuitive understanding of the RH that was simply rejected by my professors. To read such a good defense of the vague and hard to articulate aspects of human existence I found really rewarding.

Thank you for your interesting article. It left me with a question. In process of left and right are we losing sight of the integrating the two parts, corpus callosum? Based on understanding we take action and that, I imagine, comes only after integration, or else we ponder and funnel! for ever seems to me.

Sorry forgot the click the notification email. I am curious as to your thoughts, please on the corpus callosum? Where it all happens, Thanks much for enlightening us.

Hi, Nader: Our consciousness will always be a fusion of the two hemispheres – unless there is some organic thing wrong involving surgery or a stroke, etc. I guess I’m less interested and not really knowledgeable about the physiological mechanics of how it is accomplished. More about the interplay between the two modes of relating the world and integrated they need to be. Sorry I can’t be more helpful.