Taken from here

Episode Transcript

Scott Rae: Welcome to the podcast, Think Biblically: Conversations on Faith and Culture. I’m your host, Scott Rae, dean of faculty and professor of Christian ethics at Talbot School of Theology here at Biola University. Our guest today is Mr. Lawrence Reed, who is the President Emeritus of the Foundation for Economic Education. He has actually just recently stepped down from that role. I don’t think it’s quite accurate to say that you’re retired, because you’ve got lots of projects, in particular writing projects that you’re looking forward to doing over the next few years. Larry, welcome to our time today. You spent a lot of time thinking about a very provocative topic that you’ll be speaking about later at [Acton] University, entitled Was Jesus a socialist? So I appreciate the opportunity to ask you some questions about that and to flesh that out a bit for our listeners.

Lawrence Reed: My pleasure. Thank you for having me, Scott. I appreciate it.

Scott Rae: Well, let’s first define what you mean by socialism so that we’re all on the same page as we begin this discussion.

Lawrence Reed: I’m very glad you started with that question, Scott, because the views of what socialism is are all over the lot. Some people think socialism is just helping people, sharing things with people, doing good. But, of course, all of those things you can do under capitalism. That’s not enough of a definition. I think socialism should be defined as a system in which you have central planning of the economy by the government or government ownership of the means of production or the forcible redistribution of income by the government. In most cases, when you have socialism, you’ve got some of all three. Of course, the most extreme versions will have all three, where the government runs everything, owns everything, and redistributes wealth according to its liking.

In any event, no matter what version of socialism or the degree to which you have it may be, the distinguishing feature of socialism is force. If it’s voluntary, it’s not socialism. You can do that under capitalism. What differentiates socialism is that, for those various purposes that I mentioned, government is the main player, and it uses coercion or the threat of it to do its job.

Scott Rae: I think that’s a helpful definition, especially those three prongs that are to it. I wonder if maybe the best way to define socialism would be to shatter some misconceptions and tell us what it’s not. You say it’s not just a desire to help people.

Lawrence Reed: That’s right.

Scott Rae: Are there other misconceptions about socialism that we need to debunk here at the start?

Lawrence Reed: Well, I think most if not all of those misconceptions come down in some form to the idea that government is going to be helpful to people. It’s going to give them health care. It’s going to provide them employment. It’s going to give them security and assuredness for their economic lives and so forth. In one version or another, that’s what it reduces to. But what distinguishes it from any other system, from capitalism in particular, is how that is to be done. Socialism does it by means of the concentration of power in the hands of government. It doesn’t do it by voluntary civil society organizations, by mutually beneficial free commerce in the marketplace. Those are attributes of capitalism. Socialism does the job it’s supposed to do … No matter how poorly or how well, it does it through coercion, through force.

Scott Rae: So what countries would you say are predominantly socialist economies today around the world? Give us an example of some of those.

Lawrence Reed: I wish I could give you an example of one that is both socialist and that is a model in some way, but those two things don’t seem to go together. The most extreme application of socialism would be in such places as North Korea, where the government is in charge of everything. Close behind would be places like Cuba or Venezuela. But some people mistakenly claim that Scandinavia is socialist, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Norway. They have extensive welfare states, but they’re really not socialists. They have globalized economies, lots of private ownership. I have reasons to object to some of the welfare stateism and its effects, but they’re not quite socialism. So if you really want true socialism, I’m sorry, you’re going to have to look at countries that frequently employ the use of force to do things even if they seem to be good things to do.

Scott Rae: So there really aren’t a whole lot of examples of the pure socialist ideal being practiced today.

Lawrence Reed: No, there really aren’t. Those countries that dabble in some degree of socialism, usually, if they seem to be doing well, it’s not because of the socialism they have. It’s because of the capitalism they haven’t yet destroyed. So even those halfway houses still depend for what capitalism they have left to pay the bills of the socialism they have.

Scott Rae: So it sounds like what you’re suggesting is, if we looked at this on a continuum of pure socialism on one end and pure capitalism on the other, that most economies are mixed.

Lawrence Reed: That’s right.

Scott Rae: They belong somewhere along this continuum.

Lawrence Reed: Exactly. I think that describes overwhelmingly most of the countries of the world.

Scott Rae: Now let’s go back to the New Testament part, which is the heart of what you’re going to be talking about here at Acton. What in the New Testament makes people think that Jesus was a socialist?

Lawrence Reed: Some people think that, again, socialism is sharing. It’s caring. It’s compassion. It’s just people helping people. If that’s what you think, then you might be inclined to believe that Jesus was a socialist because he talked about caring for the poor and so forth. But he never once advocated the tools that socialism uses to do those things. He never advocated for the concentration of power. He never advocated for the government ownership of the means of production or the forcible redistribution of wealth or the central planning of an economy. I mean, first of all, he was interested in other things, your soul, first and foremost. But on earthly matters, Jesus never suggested in any way that he was calling for the use of concentrated political force to do good things.

Scott Rae: So it sounds like, if I asked you to finish the sentence, «Jesus was not a socialist because,»-

Lawrence Reed: [crosstalk]

Scott Rae: … that would be the main thing.

Lawrence Reed: That would be it, absolutely, never advocated the use of concentrated political force to get something done.

Scott Rae: But Jesus did advocate what I would refer to as extreme voluntary generosity, where his followers were pretty clearly mandated to hold all their possessions pretty loosely. But that’s a far cry from what you’re describing as socialism.

Lawrence Reed: Oh, yeah. I mean, he never said, «And if you don’t do it, I’m going to call Caesar and have him force you to do it.» He felt very strongly that a person doing something good from his own heart is … That’s what he was looking for. That makes all the difference in the world. You don’t make somebody a religious person by taking him to church at gunpoint. You want an inner change. You want, from within a person, a rebirth, a renaissance in such things as character and compassion. That’s what makes all the difference in the world. Jesus was more interested in what’s in your heart than he was in what you wanted a politician to do. That didn’t concern him much at all.

Scott Rae: I think that strikes most people as intuitively pretty correct, that if you’re mandating me to do something and you’re twisting my arm in order to get me to take out my wallet and give some money to the homeless guy down the street, that sort of wipes out the virtue-

Lawrence Reed: Oh, absolutely.

Scott Rae: … for me.

Lawrence Reed: What we should really want in society is people who do the right thing, do the compassionate thing because they want to, not because they have to, not because there’s a gun at their back.

Scott Rae: But the cynic would say, if we just left it to that, most people are not going to do that.

Lawrence Reed: You hear that a lot, but I reject the idea that government is more compassionate than the people it supposedly represents. There are a lot of temptations within government that often take good people and grind them up. So if anything, I think, as a rule, government is less compassionate than the ordinary citizen, less capable even of providing real care to a person in need. When you and I do it, we’re interested in things like accountability. We’re interested in the person. We’re interested in suffering with them, getting to know them. Government just writes a check and pops it in the mail. I mean, that often takes a problem and makes it worse, not better.

Scott Rae: I appreciate that that’s the idea of compassion, which is to suffer with someone, as you know. It’s the idea that we have a relationship with the person that we’re showing compassion towards.

Lawrence Reed: That’s right.

Scott Rae: All right, let’s go to the early church. A lot of people suggest that the early church held all their possessions in common and that Ananias and Sapphira, for example [crosstalk].

Lawrence Reed: Yeah.

Scott Rae: That sounds a lot like the forcible redistribution of wealth and property from that text in Acts 6, when they held something back. There were pretty serious consequences for them on that. That sounds a lot like coercion to me. How do you understand the early church and as Acts describes that holding all things in common?

Lawrence Reed: That’s right. Well, it’s clear from subsequent passages that, although the early Christians were expected to hold much in common and not to focus on material wealth, that they didn’t sell everything they had, because they continued to meet, in many cases, in their own private homes. But you have to consider the context too. This is a new faith in a hostile land, occupied by foreigners, Romans in this case, who did not like the idea of these religions popping up and challenging perhaps Roman authority. So it was very important that the early Christians have certain standards in order to be convincing, persuasive, and maybe even to keep them out of trouble sometimes from the Roman authorities. There’s nothing in the New Testament that says the way the earliest of Christians were expected to conduct their economic affairs is therefore the way that all people in all times are to conduct their affairs. Christ never said, okay, you folks, we need you to behave this way, and therefore 2,000 years from now, we want everybody doing the same. They had certain standards they had to meet at that time to get the faith off the ground. So you have to consider the context.

Scott Rae: But you would hold that there are certain moral principles, certain virtues that do transcend time and culture, like their generosity-

Lawrence Reed: Oh, yeah. I think that’s-

Scott Rae: … and their lack of materialism, things like that.

Lawrence Reed: That’s right. But, see, I think that, to be truly generous, one has to do it of his own free will-

Scott Rae: Voluntarily.

Lawrence Reed: … and of his own money. You’re not generous just because the government tells you you have to do it or because you support a politician who says he’ll get it done for you.

Scott Rae: Larry, a lot of people today are very skeptical about the accumulation of wealth, particularly about the exercise of power that goes with that. Now I think, in the first century, when Jesus and the early church were around, I think [inaudible] was a little different than today, because power was used in order to accumulate wealth, where I think today it’s more accumulated wealth is used as a means of exercising power. In some cases it just reflects cronyism and protecting yourself from competition. But there are a lot of people who hold that the Bible teaches that the accumulation of wealth itself is morally problematic, especially when you have so many needs that could be met. How do you understand the scripture on that?

Lawrence Reed: I don’t see the Bible in any way as suggesting the mere accumulation of wealth, per se, is wrong or bad. I think what determines whether it’s right or wrong is how you come about the wealth and what you do with it. I mean, if you’ve come about it through the use of political connections, where political power is employed to maybe stifle your competition or to get something from people that you wouldn’t otherwise freely get in the marketplace, then, yeah, I’d be the first to blow the whistle on that. If you use your wealth, even if it’s obtained entirely through voluntary, peaceful, productive means, but then you use it to buy political power, I’d say you’re crossing a line, that that’s a bad thing too. It all depends on how you come about it. If it’s free, legitimate, voluntary, peaceful, fine. It’s a measurement of how much, typically, you’ve contributed to the rest of society. Just don’t use it, once you get it, to oppress people through your alliance with those in political power.

Scott Rae: I think that’s a very big difference in the way wealth was accumulated in the ancient world, in Jesus’ time, and it is today, because as you know it was unusual for people to become wealthy in the ancient world without doing some of those very things that you’re referring to.

Lawrence Reed: Exactly, political connections.

Scott Rae: Or it was by theft or extortion or oppression, which I think is one of the reasons why Jesus made the statement, the remarkable statement, that it’s harder for a rich man to enter the kingdom than it is for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, not because there’s anything, as you said, intrinsically problematic about wealth. But the way in which it was obtained was so often morally compromising.

Lawrence Reed: That’s right. I think he was also saying with wealth come such things as great temptation. So he’s saying don’t allow your wealth … Even if it’s secured entirely in a peaceful, productive fashion, don’t allow your wealth to become the central object of your life. Don’t worship wealth. Don’t fall into temptation that comes with it. He says be careful. Be mindful of it. But he’d say that about a lot of things. I mean, I think he would say it’s easier for a guy in great shape to climb the fence than a man who’s broken both legs. That doesn’t mean he’s opposed to the guy who’s broken his legs. He’s just saying you’ve got more challenges.

Scott Rae: Now you cite several passages in the Gospels that have a lot to do with economics, where Jesus either makes economic assumptions or is directly teaching about some aspect of economics, so things like the parable of the talents, the good Samaritan, the parable of the workers in the vineyard, rendering unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s. So if we could, spell out a little bit further. What do you think Jesus had in mind about economics with the parable of the talents? We’ll start with that.

Lawrence Reed: I think Jesus was primarily calling us all to very high standards of character. He wasn’t opposed to the accumulation of wealth. He wasn’t opposed to entrepreneurship. I wasn’t opposed to the wealthy, per se. Again, it’s all a matter of how you obtained your wealth and what you do with it. In the case of the parable of the talents, he tells the story of a man who is leaving his estate for a time. He trusts three men with a substantial but equal degree of his wealth. He says I’ll be back later and see what you’ve done with it. He comes back later, and he finds that one man has not magnified the wealth in any way. He has the same amount, but he’s proud that he’s preserved the master’s wealth. The second guy actually put it to work, made some investments, and he’s got two or three times what the master originally entrusted him with. The third guy did an even better job at investing it and has 10 times as much. Well, if Jesus were a socialist, he would upbraid and excoriate the third guy for focusing on the accumulation of wealth. But, instead, in the parable, he actually condemns the first guy for his non-creation of wealth.

Scott Rae: For burying it in the ground.

Lawrence Reed: Exactly, yeah. He says the third guy is the hero of the story, and the guy from whom … Jesus says we’re going to take the talents, the money from the first guy, and give it to the third guy, because he knows how to create wealth. A socialist would never come to that conclusion.

Scott Rae: So a socialist would completely level the playing field in terms of outcomes.

Lawrence Reed: At the very least. He might even go a step further and condemn the third guy for being so productive.

Scott Rae: All right. What about the parable of the good Samaritan. That one, I think, is a little harder to see what the direct connection would be.

Lawrence Reed: Well, think of the story. A man is on the road, and he comes across a man who’s in desperate shape, perhaps beaten, robbed, laying along the side of the road. He clearly needs help. The man who becomes known as the good Samaritan, what does he do? Or what does he not do? He doesn’t say to the man in need, «Oh, well, you need to find a social worker,» or, «Maybe there’s a government program for you,» or, «I’ll drop in a word with the emperor to come back and do something for you.» No. With his own resources, of his own free will, he immediately pitches in and helps the man. If he had done any of those other things, if he had just said, oh, it’s somebody else’s responsibility, it’s the government’s, or I’ll get a program going for you, we would not think of him today as the good Samaritan. We would think of he as the good for nothing Samaritan. But he’s the good Samaritan because he helped the man from his own free will and with his own resources.

Scott Rae: Sometimes I think what we forget about that is that compassion to really make that work requires economic capacity to be able to do that. Obviously, his funds were not unlimited. But as I understand it, he essentially did the equivalent of giving the innkeeper his credit card, saying whatever charges he has, put it on my bill.

Lawrence Reed: Yeah, good way to put it. If he had been poverty stricken, he couldn’t have done [crosstalk]

Scott Rae: He couldn’t have done any of that. So I think sometimes we assume that the systems that are the most productive are also the least compassionate, which, I think, in reality, I think just the opposite of that is true, because it’s the systems that produce wealth that are able to generate the resources not only for the taxes needed for government, but also for private charity and things like that. What about the parable of the workers in the vineyard. That one is a little more puzzling, because that seems patently unfair [crosstalk] what Jesus is prescribing there.

Lawrence Reed: It’s a fascinating story or parable. When I first read it, I remember just thinking, as an economist, wow, there’s a lot of things going on here. There’s supply, demand. Anyway, the story goes like this. A man needs to hire workers to help bring in the harvest, presumably, grapes. So he hires workers as the start of the day and offers to pay them a day’s wage. But partway through the day, he realizes, oh, I haven’t got enough workers, and I’ve got to get this harvest in. So he hires another group of workers maybe halfway through the day, and to get them, he offers to pay what he had paid the other ones for the whole day, or offered to them.

Finally, with an hour left in the day, he realizes, oh, my gosh, my harvest is going to not all get in if I don’t hire a few more workers. So he hires some others just for an hour, and he offers to pay them what he offered the first group to work all day. Some of those first group come to him later and say, hey, this is not fair. These guys have only worked an hour. Or the ones that only worked half a day, you paid them as much as you paid us to work all day. The response is not, oh, yeah, you’re right. I have to even this up. The response is, I didn’t cheat you. I paid you what I offered, and you accepted. It’s my money.

What’s going on here, I think, is a defense of contract, two people arriving at a mutually beneficial contract. It’s supply and demand. I mean, the guy needed more workers, and to get them at the end of the day, he had to pay what he had to to attract the workers. There’s freedom of association here. If Jesus were a socialist, he would have the master being criticized for not paying a proportionate wage. So he arrived at a very un-socialist and pro-capitalist prescription at the end of the day.

Scott Rae: I think that’s a really good observation, because I think most people don’t see readily in that parable an affirmation of private property [crosstalk]

Lawrence Reed: No [crosstalk]

Scott Rae: It’s the owner’s money, and this is what he needed to do to attract labor at the last minute, or else the harvest was not going to be complete.

Lawrence Reed: He kept his word to everybody. What he offered is what he paid.

Scott Rae: Now I’ve got some colleagues who are from Canada, and I’ve got several friends and neighbors who are from Scandinavia. In fact, my son had a roommate for a while who was from Sweden. I think, for one, it’s not uncommon for them to claim that their countries are actually socialist countries. We’ve talked about that, that that’s not really accurate, because throughout Canada and throughout most of Western Europe, the balance between government’s involvement in the economy versus the individuals is different than it is in the US. So I asked one of these friends, «So tell me what the tax rate that you pay is in Canada.» I thought that would be a drop the mic moment when this person said about 50%, but it wasn’t. The reason it wasn’t is because this person, I think, actually made a fairly compelling case that they have just agreed to a different tradeoff than we have in the US. They are content to pay much higher taxes, but they have much higher expectations about what government will provide, particularly in terms of health care and other things. What’s wrong with that arrangement? It just seems like it’s just a different social contract that people have somewhat, I think, voluntarily agreed to because they’re counting the cost of their taxes but the benefits that those bring to them.

Lawrence Reed: Well, first of all, you can’t say it’s voluntary across the board. I mean, if there’s one person who says, hey, I had a better use for those dollars than what the government put them to after it took them. So it’s not entirely voluntary. It’s that some majority of the people who actually voted supported politicians who delivered that. But keep in mind too that even in those Scandinavian countries, that consensus has evolved over the years. They have less of a welfare state, less sky-high taxation today than they had 30, 40 years ago. They tried the 90%, 99% tax rates, and they found that that was disastrous.

Scott Rae: Because?

Lawrence Reed: Well, because it drove the most productive people away. It stifled the formation of new businesses. It led to chronically high unemployment. So Scandinavia, all those countries, in fact, have been reducing tax rates much of the last 20 years. They’ve gone the other direction and found it wanting. Nonetheless, they, generally speaking, I think it’s fair to say, have decided they’re willing to accept a lot more welfare state than I am or even the average American. Maybe that’s less objectionable when you’ve got a homogenous population that may not be as entrepreneurial as America. America has a long history of people who are willing to take great risks. We had a western frontier where people had to put everything on the line to go west and so forth. So we are a naturally more risk-taking, entrepreneurial people, I think, who don’t respond well to sky-high taxes.

Scott Rae: Because it skews the calculus of risks and benefits.

Lawrence Reed: Exactly. At some point, people are going to say, look, if I don’t get to keep the rewards, why should I take the risks?

Scott Rae: I think there are some who would say I don’t even want to work harder, because the harder I work, the more I make, the less I get to keep.

Lawrence Reed: Exactly, yeah.

Scott Rae: I think that’s helpful. I think it’s helpful for our listeners to recognize that, when we talk, that every tradeoff has costs to it. My Canadian friends think it’s morally reprehensible that so many people can be bankrupted by health care bills, but I wouldn’t be thrilled. I actually thought when this person said that they paid a 50% tax rate that that discussion would be over. But that’s not necessarily true.

Lawrence Reed: I wonder how many people go bankrupt for other reasons after the government takes half their money.

Scott Rae: That may also be true. I guess, one last question. I know historically, if you look throughout the 20th century, there have been periods where, throughout the world, people have romanticized socialism. What would you say? What advice would you have for people, say, in our Millennial, Gen Z generation today who seem to be romanticizing socialism again like people did in the 1920s and 30s? What advice would you have for them?

Lawrence Reed: Well, I would start by acknowledging that, with few exceptions, they have good intentions. But I would encourage them to be thorough in their thinking. By being thorough, I mean think of things like all people, not just a few. Sometimes we fall for the thing that may seem to work for a handful of people while ignoring the effects on everybody else. I would encourage them also to think long-term, because there are a lot of things you can do in the here and now for the moment that may seem to be good. But what if they have as a long run consequence the bankruptcy of the country? Would you say, well, that’s okay, we’ll just deal with it when we get there?

A lot of civilizations that have gone the welfare state route, for instance, they started out on that path thinking, oh, we’re going to help people. The ancient Roman republic went the welfare state path. If you could go back to the Romans and say, you know, you started out with good intentions when you started the grain dole and the other handouts. But I have to tell you that you ended up bankrupting the morals and the economics of your society, and you got conquered, and you’re off the map. You maybe ought to rethink that. But, of course, they can’t do that, but we should not be so blind to the lessons of history and economics and thinking long-term. We should look very carefully at all the consequences of all acts and policies, not just what seem to be beneficial for a few in the near run.

Scott Rae: Well, this is very helpful stuff, very insightful. What I appreciate is that you trained as an economist, but yet your grasp of the New Testament and the life of Jesus is really good.

Lawrence Reed: Well, thank you.

Scott Rae: I appreciate the way you have tried hard to integrate your study of the Bible and your example of the life of Jesus into your economic theory in some really meaningful ways. So I think this will be really helpful for our listeners to think about this not only from someone who’s good in economics, but also has a good grasp of the New Testament.

Lawrence Reed: Well, thank you, Scott. I appreciate that.

Scott Rae: I appreciate both of those aspects coming out in our time today. So we’re really grateful for the chance to ask you some questions and to spell out some of these things for us in a little bit more detail. It’s much appreciated.

Lawrence Reed: My pleasure.

Scott Rae: This has been an episode of the podcast, Think Biblically: Conversations on Faith and Culture. To learn more about us and today’s guest, Lawrence Reed, and to find more episodes, go to Biola.edu/ThinkBiblically. That’s Biola.edu/ThinkBiblically. If you enjoyed today’s conversation, give us a rating on your podcast app and share it with a friend. Thanks so much for listening, and, remember, think biblically about everything.

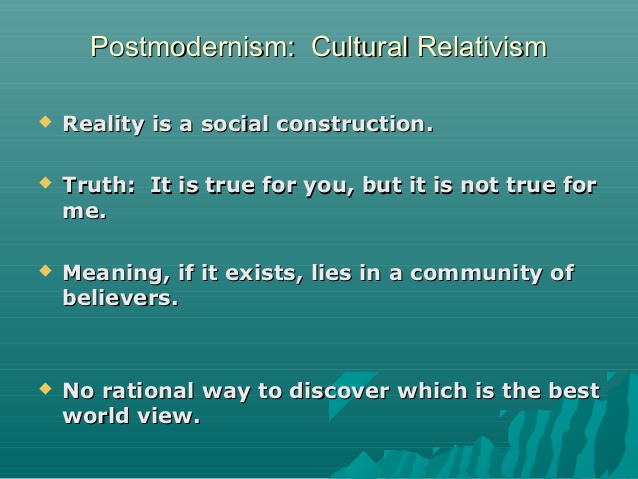

Taken from famous atheist philosopher John Searle’s book “Mind, Language And Society: Philosophy In The Real World”,

Taken from famous atheist philosopher John Searle’s book “Mind, Language And Society: Philosophy In The Real World”,

Bing Crosby singing White Christmas for the first time in the movie Holiday Inn

Bing Crosby singing White Christmas for the first time in the movie Holiday Inn In the movie the real Rudolph is featured as a drunk

In the movie the real Rudolph is featured as a drunk Comedian Jackie Mason compares Christians to cows

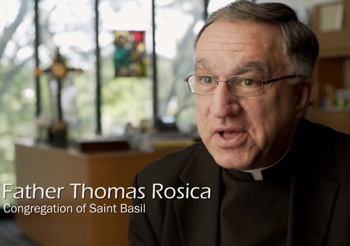

Comedian Jackie Mason compares Christians to cows Rosica: the Church does not own Christmas & approves its commercialization

Rosica: the Church does not own Christmas & approves its commercialization